There is a lot of talk, and words written, about natural wine these days and it seems to be all the rage. I’m no exception to this as I have tasted quite a few natural wines, then written about them here. I therefore felt compelled to write a few words about my thoughts on natural wines, including my definition of natural wine based on my experience and my beliefs.

Having visited Vini Veri, “Vino Vino Vino” in Verona earlier this year, I saw this trend in full swing. Lots and lots of “natural” wines, many of which were not in my opinion well-made. Others didn’t fit my definition of natural.

I will begin with my definition of a natural wine:

A natural wine should be made first and foremost by a winemaker who has the right attitude and philosophy. It matters little to me whether or not the winemaker is certified organic or recognized by Demeter as biodynamic. I am not excluding these winemakers here, merely stating that getting certified or recognized by Demeter is sometimes not possible due to vineyard treatments by neighbors or is sought out for the wrong reasons, like marketing rights or government subsidies. Therefore, I feel that it is more important that the winemaker understands natural wine making and has the correct philosophy. The wine-maker wants to do the right thing. It’s not important to me that the label states that the wine is biodynamic or organic.

Second, natural winemakers should never use pesticides in the vineyards. They should work as naturally as possible in the vineyards which can include green harvesting and canopy management. It can include other measures to insure healthy plants which should in turn produce healthy grapes. They should even limit natural fertilizers whenever possible. Biodiversity should be encouraged, not destroyed.

Wild boar footprints in the Roagna vineyards suggesting biodiversity - photo by Vinosseur

Third, the grapes should be harvested by hand and not machine. Hand selection of fully ripe and healthy grapes is an important step in producing a great wine.

Fourth, the grapes should then be crushed and left to macerate on the skins for an extended period of time before pressing to help stabilize the wine and preserve the wine once bottled. This statement is not from personal wine-making experience but from my reading and talking to respected wine-makers. Most of the natural wines I have tasted have had extended skin contact for the above mentioned reasons.

Fifth, the grapes should ferment with indigenous (wild) yeasts, not added (selected) yeasts. Healthy grapes will have these indigenous yeasts on their skins. I do feel however, that it’s ok to add a natural/neutral yeast to start the fermentation process if it does not commence on its own. Natural wine makers whom I respect, have the right philosophy and work as naturally as possible have had to do this on occasion.

Six, the fermentation should take place without any artificial temperature control. Of course the wine-maker may chose an ideal place to ferment the wine. If you are doing this in the cellar where the average temperature is quite constant, this is a sort of “temperature control”, and is ok in my opinion.

Grapes macerating in Amphorae. Photo courtesy of Doug Wregg of Les Caves de Pyrene

Seven, “oak” (barriques) should not be used. When I speak of oak, I am referring to barrels smaller than 600 liters. Of course, it also depends on the age of the barrel. If the barrel is only 200 liters but is 100 years old, I suppose that there will be no influence on the wine except for the exchange of oxygen, and this is ok. Oak, especially new, adds unwanted elements (flavors) to the wine and also softens tannins, for these reasons I don’t think a wine is natural if it’s been fermented or stored in oak. I want to clarify one thing here to those who might be reading this and thinking “this guy obviously hates oak”. The point of this rule is that I am against the use of oak in natural wine because although oak comes from trees and in and of itself is a natural product, the oak is then toasted. Once the wine comes into contact with this finished barrel, the wine changes. I personally feel that this is completely unnatural. So, for my definition of natural wine, I feel that other fermentation/storage mediums should be used, like cement, amphorae, steel etc.

Eight, a natural wine should be neither fined nor filtered before bottling. This in my opinion is an important rule. Why take anything from the wine?

Nine, a natural wine should not have any added sulfur. This is probably the most controversial point. Many producers are adding only 10 or 12 mg of sulfur (10-12 ppm) at bottling, and I am grateful that less and less sulfur is being added to wine, but adding sulfur is not natural and therefore for me to consider a wine completely natural, there can be no added sulfur. This being said, even a wine with no added sulfur will still contain sulfur since it is a by-product of fermentation. I also feel it important to mention that although in my definition of natural wine there can be no added sulfur, there are many great wine makers who add a few milligrams of sulfur at bottling and I enjoy these wines on a daily basis.

That’s my definition of natural wine. Therefore, with regards to this website, I will never categorize a wine I taste as “natural” unless it adheres to the guidelines I have laid out above. Many of the wines that I do not categorize as natural, may to others be regarded as natural. I have to add that I do not and have not ever made wine, so I realize that my definition might seem rather simplified to some.

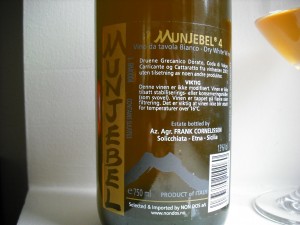

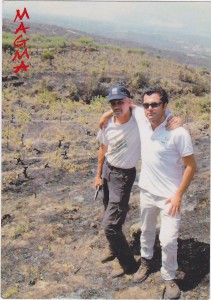

As with any trend, there are leaders, followers and imitators. I feel the clear outspoken leader in the natural wine world is Frank Cornelissen from Mount Etna in Sicily. I have written about him and his wines more than once here on my website. Another leader in my opinion is the Domaine Le Mazel in the Southern Rhone who have been making wines without the addition of Sulfur since 1998. Although less well known than Cornelissen, their Cuvée Raoul is one of the greatest wines I have ever tasted. I will do a thorough profile and tasting note on this wine on this site in the very near future.

There are the followers. These are the great winemakers who are more recently involved in natural wine making and in my opinion are doing a great job and making huge strides towards excellence. These wine makers also adhere to the above mentioned rules I feel should be followed.

Then there are the imitators which I saw plenty of at Vini Veri and continue to see on a daily basis. For one, some of these wine makers insist on fermenting and storing their wines in oak (barriques). At times even using new oak. How is this natural? Now, I find it important to state again that I am not against the use of oak. I am simply against the use of oak in natural wine making. I also want to state that I am not accusing these wines as being “bad”. I have tasted many excellent wines which are almost natural and have been aged in oak. And second, some of these natural wines are just poorly made.

Finally, I feel that some people just don’t understand natural wine. I am happy that natural wines are becoming trendy, but as with any trend, there are many bad copies. Not all natural wines are good. I may offend some people by these statements and this isn’t my intent at all. I am simply stating my opinion. I welcome comments and an open dialogue with anyone who feels otherwise.

To sum up, natural wine should be fermented grape juice. Nothing taken, nothing added.